The History of Cookbooks and Where We Are Today

Almost every home I visit hosts an eclectic mix of cookbooks, from one-pot keto guides to faded, hand-written family heirlooms. The cookbook shelf seems to me a quiet way of peeking into someone’s life, understanding how they spend time in the kitchen or with whom they share their secret recipes like prized relics. A household staple, cookbooks that float to and from strangers, loved ones, and children hold a seemingly universal and connecting role in our modern lives. However, it hasn’t always been this way. Like many elements of life that may seem commonplace, the cookbook at one time was a privilege for the wealthiest and the richest, a demarcating line between noble, middle-class, and poor.

The Truncated History of Cookbooks and Class

Before exploring some of the history of cookbooks, I want to mention that I’ll be speaking narrowly about the Western history of cookbooks, since those are what’re most readily available and published. The first recorded cookbook is said to be four clay tablets from 1700 BC in Ancient Mesopotamia, but by the 1300s, cookbooks were a norm for kings and nobles. In 1390, Forme of Cury (The Rules of Cookery) was published for–but not by–King Richard II. It contained recipes by the master-cooks, which you can see published in the 1780 print version here. In this cookbook, elements of southern European cooking surface–saffron, sugar, almonds, and various pasta recipes. Imagining what it would be like to taste and concoct these recipes is exciting, like indulging in the rich taste of the past. But it’s important to note that these ingredients, prepared and created by lower-class, were enjoyed solely by the rich bourgeoisie, carrying with them a fraught history of classism and exclusivity.

Photo source: https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbc0001/2010/2010pennell31282/0008r.jpg

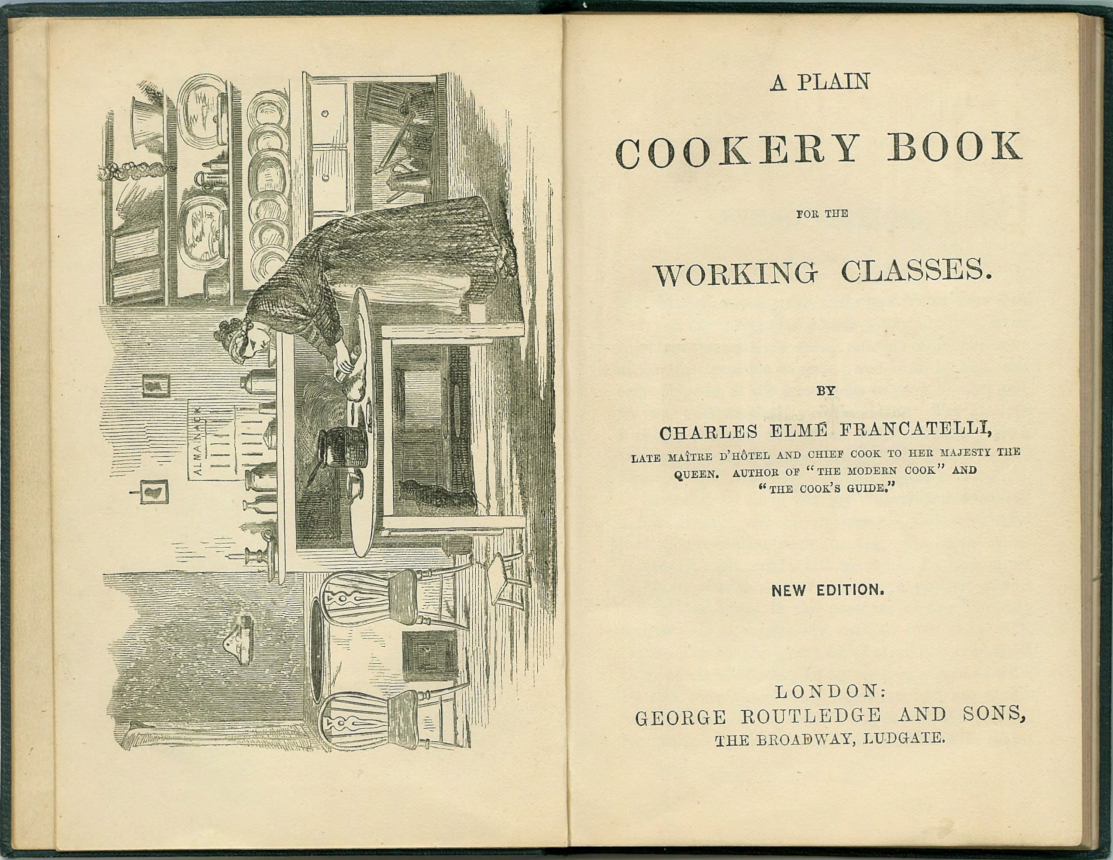

As mass printing and publishing increased by the 15th century and public literacy increased by the 17th century, cookbooks became less of a luxury, and somewhat of a standard. However, just because there was increased availability did not mean there was increased access. The type of recipes varied significantly according to class. The titles of cookbooks exemplified the role they played in perpetuating social hierarchy between the rich and poor, like in titles such as “Plain Cookery for the Working Classes,” “The Poor Man’s Larder and Kitchen” or “Fifteen-Cent Dinners for Working-Men’s Families” to name a few. On the other hand, recipes and books like “Les Soupers de la Cour” and “La Cuisiniere Bourgeoise” for royals and aristocrats.

Photo source: http://collection.hht.net.au/images_linked/48266.jpg

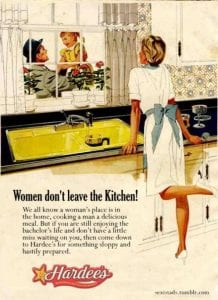

As the World Wars commenced in the early-mid 1900s, food gained a new meaning: they were about thriftiness, preservation, rationing, and efficiency. But after World War 2 as men came home and women were then expected to be traditional housewives, a domestic and feminized ideal in the kitchen and cookbooks emerged, coinciding with the rise of industrialized, canned, and processed food. This linked article outlines that in the 1950 Betty Crocker’s Picture Cookbook, the book says that “Just as every carpenter must have certain tools for building a house, every woman should have the right tools for the fine art of cooking.” Throughout these post-war cookbooks, it was clear that much of a woman’s worth was determined by her husband’s judgements of her adequacy as a mother, wife, or cook to her husband.

Photo source: https://sites.psu.edu/rclblogmgh/2018/09/06/bad-ad/

Now today, with the rise of Food Network and other food media like the Bon Appetit Test Kitchen, making meals seems trendy in a way, with a niche for everyone–vegans, meat-eaters, health nuts, and dessert geeks. As recipes and cookbooks have become digitized and integrated into our entertainment schema, they are possibly more normalized and maybe less explicitly allocated for rich or poor or male or female. However, one could argue that class issues are not fully erased. As discussed in last month’s blog, just because food information exists doesn’t mean it’s readily available or distributed evenly. Recipes often contain expensive and exclusively ingredients, which make them inaccessible for low-income or food apartheid communities. Having a familiarity around and access to a variety of recipes and cookbooks is a privilege, and not one which all folks possess as many communities have been ostracized from farmers markets and bookstores for the sake of fast-food and convenience stores.

Racism and Exclusivity Today

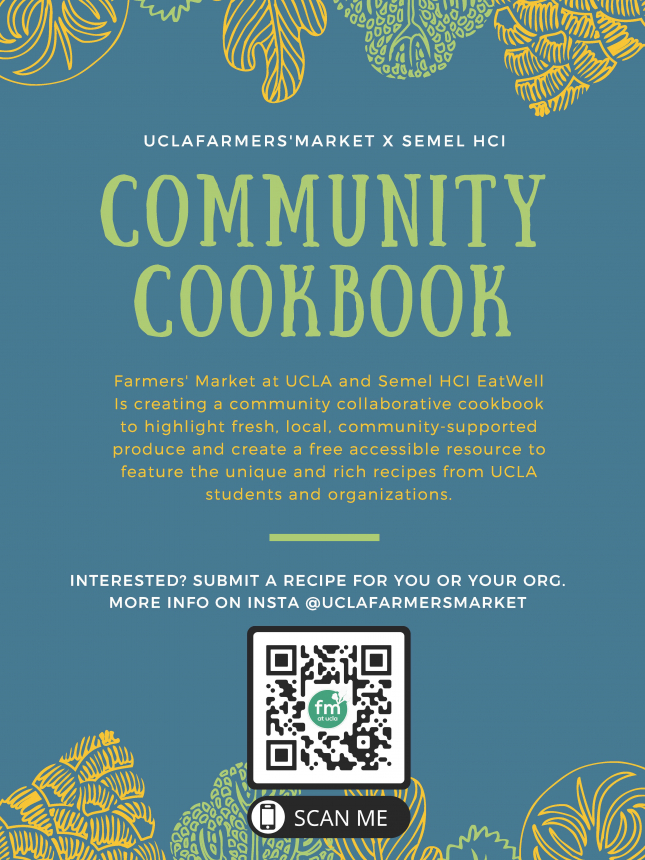

In exploring the history of cookbooks throughout time, I would be remiss in not acknowledging that many recipes that circulated amongst white and wealthy families came from Black slaves; these books which we now see as a simple exchange of recipes are in many ways products of subjugating a race of people. This isn’t an extinct phenomena; it exists today when we witness the persistent reliance on Black Americans in growing, harvesting, and cooking food in the US or the racist “mammy” imagery reinforcing racial and gender roles in products “Aunt Jemima.” As explored in the link above, Black farmworkers who produce our very food are still experiencing abuse and maltreatment at the hands and the skewed benefit of their often white employers. Furthermore, the example of Aunt Jemima’s maple syrup, a name which has only just recently been replaced, illustrates how giant food corporations, like Quaker and PepsiCo, have abused racist imagery as a marketing tactic for their sole profit. Although carrying a fraught, classist, and often sexist history, modern cookbooks hold a potential to decentralize and democratize meal-sharing. By re-interpreting the purpose of compiling recipes and the way we exchange cookbooks, we reclaim and revolutionize food knowledge. There’s something comforting and exciting about the story behind recipes– the paragraph or two that hooks readers or listeners about why this recipe holds significance. It brings a meal to life, connecting us intimately with the food and their stories. And these stories behind our food matter: they transform food into something more than sustenance, but as a way of understanding each other, telling stories, and caring for each other. That’s why UCLA Farmers Market x Semel Healthy Campus Initiative Eatwell are collaborating to create a free, accessible community cookbook. We are featuring recipes from various students and campus groups to tell the story of meals, to support local farmers, and at large, to illustrate the diversity of voices and experiences that UCLA offers. We would love you to feature your own! We want you to share your story, and we want a space to collect recipes for free and for everybody.

Kayleigh Ruller is a third-year Human Biology and Society student, minoring in Food Studies at UCLA. Outside of Semel Healthy Campus Initiative, she leads the UCLA Farmers Market team, makes podcasts, and writes about the intersection of food, health, and culture. She finds inspiration by trying all the different restaurants in LA, drinking coffee to stay motivated, and cooking with her roommates in her free time!

References:

Notaker, Henry. “A 600-Year History of Cookbooks as Status Symbols.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 27 Oct. 2017, www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/10/cookbooks-status-600-years/544164/.

“Shedding Light on Black and African American Farmworkers.” Farmworker Justice, www.farmworkerjustice.org/blog-post/shedding-light-on-black-and-african-american-farmworkers/.

Staves, Dana. “A Brief History of Cookbooks Worldwide.” BOOK RIOT, 19 Nov. 2019, bookriot.com/history-of-cookbooks/.

Fabrizio, Lauren E.. “Exploring the Domestic Ideology of the Postwar Era through Cookbooks.” (2015).